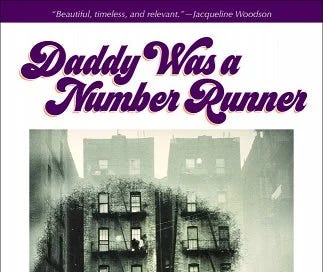

Daddy Was a Number Runner, published in 1970 by Louise Meriwether, is a coming-of-age novel about a young girl in Harlem during the Great Depression. Though this novel is not autobiographical, Meriwether, born in 1923, wrote of her own generation.

Daddy Was a Number Runner stands among other coming-of-age novels written by Black women about life in the United States, such as Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks (1953) and Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall (1959). Daddy Was a Number Runner also stands as a counterpart to Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn: both novels have heroines called Francie. Both girls live in poverty. Both have hardworking mothers who dream of giving their children better lives. Both love to read and earnestly desire a college education. While A Tree Grows in Brooklyn takes a Tristram Shandy-esque view of its Irish-American heroine from her conception to young adulthood, Daddy Was a Number Runner looks at the life of Francie Coffin from age 11 to 13.

The numbers game was a form of lottery played in working-class communities across the USA since the nineteenth century. A number runner like Francie’s father James Adam transported bets and winnings.1 Francie takes pride in her father’s work: “People were always asking me if I knew what number was out, like I was somebody special, and I guess I was. Everybody liked an honest runner like Daddy who paid off promptly….A number runner is something like Santa Claus and any day you hit the number is Christmas.” (13)

James Baldwin’s introduction to Daddy Was a Number Runner explains how Meriwether vividly renders “the helpless intensity of anguish with which one watches one’s childhood disappear.” (5) Francie is eleven at the beginning of the novel, and her childhood is chipped away, piece by piece. There’s crime in her neighborhood, even murder. She is molested yet can’t confess to adults due to shame and fear. Though she shows aptitude in coursework, her white teachers discourage her from aspiring to be a secretary. While Francie does not truly “come of age” in Daddy Was a Number Runner, her childhood is over by the end of the book.

The motif of illegal gambling (though Francie wonders why gambling was legal at the racetrack and not in Harlem) explains part of the lived experience of Black life in Harlem during the Great Depression. Living required taking a chance, a nearly foolish hope that tomorrow would be better, even without any assurance of stability.2 Steady work was hard to find in a global economic depression, which made one’s daily bread uncertain. Francie voices the thought of everyone who had come north during the Great Migration: “This was the promised land, wasn’t it?” (135)

What I find so compelling about Francie in Daddy Was a Number Runner is the richness of her interior life. Without ignoring the troubles of living, Francie refuses to despair, keeping the novel from having a hopeless edge. She celebrates Black life though poverty, racism, and crime make the streets treacherous. Toward the end of the novel, Francie walks to school with her friend Maude, whose teenage brother Vallie might be condemned to death.3 Francie says, “‘You gotta have faith.’ That’s what Mother had told Mrs. Caldwell so I said it again, as much to keep me from crying as to help Maude ‘cause deep down I felt just like she did.” (193)

That is Francie’s gift: even when she feels despondent, she “keeps on keeping on”4 and helps others keep on, too. At the end of the novel, Francie and her friend Sukie face the options for their lives that seem preordained: “Either you was a whore like China Doll or you worked in a laundry or did day’s work or ran poker games or had a baby every year.” (207) Yet, Francie has already begun to dream. Her mother told her, “You don’t have to do no domestic work for nobody, Francie….You finish school and go on to college….What they think I’m spending my life on my knees in their kitchens for? So you can follow in my footsteps?” (191)

The novel ends before we learn what Francie did with her life. Even after showing her readers all the difficulties of Harlem life during the Great Depression, Meriwether stands in silent testimony to a better life. She graduated from New York University with a BA in English, and an MA in journalism from UCLA. She wrote for Essence, worked in Hollywood, and taught creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College and elsewhere. On October 10, 2023, Meriwether passed away at the age of 100. One can easily imagine book-loving Francie using her pen to write a better ending to her own story, too.

In Francie’s day, the Harlem numbers game was run by Stephanie St. Clair, Madame Queen in the novel.

From James Baldwin’s introduction: “We have seen this life from the point of view of a black boy growing into a menaced and probably brief manhood; I don’t know that we have ever seen it from the point of view of a black girl on the edge of a terrifying womanhood. And the metaphor for this growing apprehension of the iron and insurmountable rigors of one’s life are here conveyed by that game known in Harlem as the numbers, the game which contains the possibility of making a ‘hit’--the American dream in black-face, Horatio Alger revealed, the American success story with the price tag showing!” (5) There are several coming-of-age novels by and about Black women that predate Daddy Was a Number Runner.

“‘They gonna kill him,’ she said. ‘They gonna keep messin’ around but in the end they gonna kill him.’ I knew what she was talking about….Governor Lehman said he wasn’t about to change the death sentence for boys under twenty-one. He said he couldn’t see no difference between the guilt of a man and a boy, so that petition the white folks sent to him wasn’t gonna save a soul. There was ten boys waiting in the death house in Sing Sing, counting Vallie and the Washington brothers, and now they wouldn’t have long to wait.” (192-193)

From Baldwin’s introduction: “[Meriwether] has so truthfully conveyed what the world looks like from a black girl’s point of view, [and] she has told everyone who can read or feel what it means to be a black man or woman in this country. She has achieved an assessment, in a deliberately minor key, of a major tragedy. It is a considerable achievement, and I hope she simply keeps on keeping on.” (7)

I've never heard of this book or author. I'm so glad you brought it to my attention, Melody. I love Maud Martha and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.