As it is for so many others, Little Women is one of my most formative books. My childhood copy has a chocolate ice cream stain right in the middle, and Barbara Caruso’s narration is the voice I hear when I read Little Women even now. In my quest to enter into the fictional world of the March family, I read The Heir of Redclyffe by Charlotte Mary Yonge, the novel Jo reads while eating apples and crying in chapter three, “The Laurence Boy.”1

I expected a fun romp through Victorian England when I began The Heir of Redclyffe. What I found alongside the fun was a novel of profound spirituality, the most convincing inspiration for the character of Laurie I’ve yet encountered, and more than a little evidence that Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) found Yonge a model for her writing for young people.

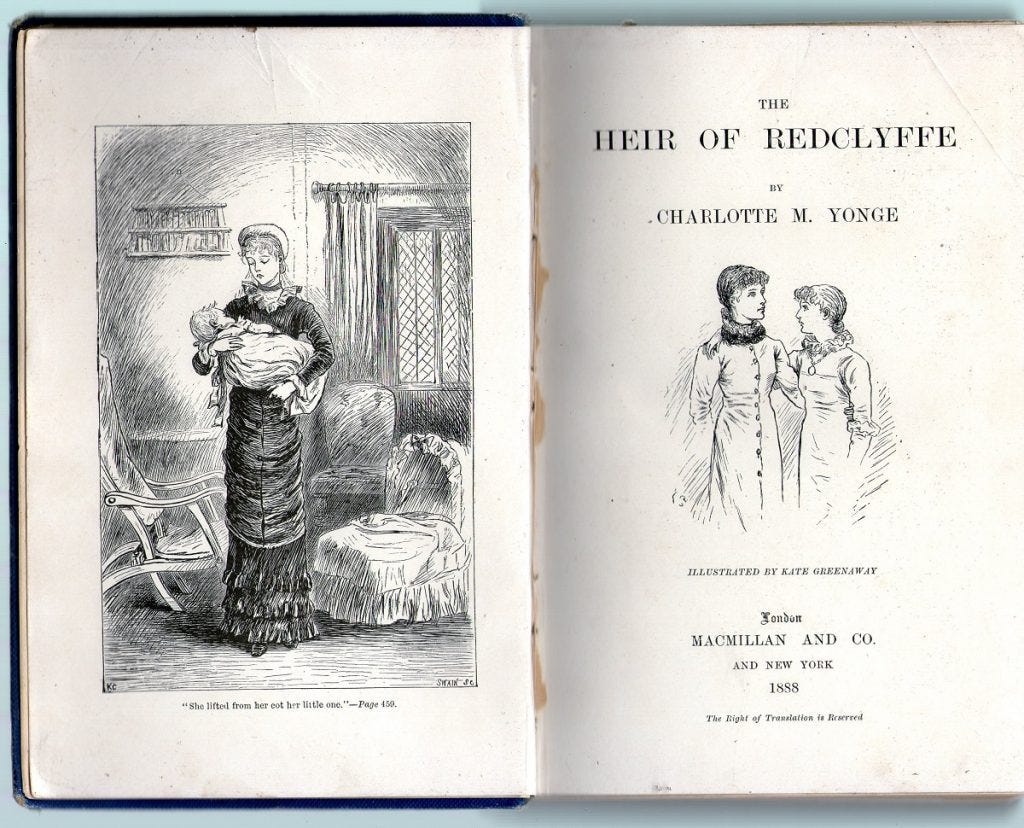

Charlotte Mary Yonge

Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823-1901) was a prolific Victorian novelist whose work was widely beloved in her own day. Her erudite father educated her at home, where she learned ancient and modern languages and advanced mathematics. Yonge was a faithful Anglican her whole life, and in her twelfth year John Keble became her parish priest. Keble prepared her for Confirmation when she was fifteen. Within a month of her Confirmation, Yonge published her first novel.2 Keble was the author of The Christian Year (1827), a collection of poems for the liturgical year. Keble’s poetry was shepherded by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and in turn Keble encouraged Yonge in her writing.

Keble was part of a movement within Anglicanism called Tractarianism that returned to high liturgy and historic forms of worship.3 His influence is deeply felt in Yonge’s life and work. Yonge’s characters live in the Christian year, arrange their weddings around liturgical celebrations, bequeath prayer books with meaningful inscriptions, and live out their piety at church and at home. In service to her deep faith, Yonge wrote dozens of novels steadily through her life.

Yonge’s work has been noted for its “stiffness,”4 though one wonders if that is a (mistaken) impression of Victorian culture in general and not an accurate representation of Yonge’s own writing, which the weeping Jo found emotionally resonant. I found The Heir of Redclyffe flows smoothly, if not always swiftly. As a reader who grew up on Alcott, Yonge was just as easy for me to read. Yonge favors shorter sentences compared to her contemporaries, and is not given to overusing long words.5 Her characters are memorable and lively, even if she does “make goodness attractive”6 instead of exploring the dark side of life.

Guy Morville, Jo March, and Theodore Laurence

The Heir of Redclyffe (1853) was Yonge’s sixth book, a dramatic tale of family, inheritance, and personal prejudice. It is hardly gothic, but contains elements that her readers would recognize from wildly popular gothic fiction: an ancient family home in need of repair, a shipwreck, a generational feud, and more. I understand why Jo couldn’t put the book down.

The titular heir of Redclyffe is Guy Morville, whom E. M. Delafield describes as “the young mediaeval knight of [Yonge’s] romantic fancy, translated into contemporary flesh-and-blood.”7 Guy’s father ran away and married a musician whom Guy’s grandfather rejected, causing a split in the family. When Guy is orphaned, his grandfather takes Guy in and raises him in the ancestral home of the Morville family. Once Guy’s grandfather dies, Guy, still underage, goes to live with the Edmonstones. There he meets his cousin and self-declared rival, Philip Morville, the orphaned son of an archdeacon who maintains the feud in the Morville line, despite Guy’s best efforts toward reconciliation.

Yonge describes Guy as follows:

He had the unformed look of a growing boy, and was so slender as to appear taller than he really was. He had an air of great activity; and though he sat leaning back, there was no lounging in his attitude, and at the first summons he roused up with an air of alert attention that recalled to mind the eager head of a listening greyhound.8

Guy has light hair and a fair complexion, while Alcott gives Laurie dark hair, but Amy March’s drawing of Laurie calls Guy Morville to mind:

Only a rough sketch of Laurie taming a horse; hat and coat were off, and every line of the active figure, resolute face, and commanding attitude, was full of energy and meaning.9

Alcott places Jo’s reading of The Heir of Redclyffe at the beginning of chapter three, which is called “The Laurence Boy.” Besides their biographical similarities, Guy and Laurie exhibit similar moodiness, musical talent, struggle to command their strong emotions, and affection for sisterly friends called Amy. While theories for the origin of Laurie in Alcott’s imagination abound, and she certainly drew from several sources, the one I find most compelling is Guy Morville, due to the evidence Alcott herself placed in Little Women.

Alcott must have seen patterns from her own family in The Heir of Redclyffe. The Edmonstones have Charles, an invalid;10 Laura, the eldest and most beautiful; Amabel (Amy), intellectually curious and active in nursing her brother; and precocious Charlotte, who has an outsize affect on the plot for so small a person. Guy’s similarity to Laurie is also his similarity to Jo—similarities that keep Jo and Laurie from marrying each other. The characters in The Heir of Redclyffe struggle with anger, like Jo, and their individual paths to moral reform remind me of the Marches’, which flow from Alcott’s Transcendentalist beliefs on self-improvement.

Spiritual Chivalry for Bookworms

In chapter one of Little Women, the March girls share their hopes for Christmas gifts. Beth wants music, Amy wants Faber’s drawing pencils,11 Meg wants unspecified “pretty things.” Jo wants Undine and Sintram, a book I fruitlessly hunted in my adolescence. Little did I know that The Heir of Redclyffe would lead me to the answer.

In The Heir of Redclyffe, Guy reads the tale of Sintram. Laura says of Guy’s reading, “he fairly cried over it so much, that he was obliged to fly out of the room. How often he has read it I cannot tell.”12 This tale becomes part of Guy’s self-understanding. Later in the novel, a baby is baptized Mary Verena after the Virgin Mary and Verena from Sintram. In the world of Little Women, The Heir of Redclyffe likely provides the source for Jo’s longing for a copy of Sintram’s tale.

Sintram and His Companions: And Undine was written by Friedrich de la Motte Fouque, and was published in English with an introduction by none other than Charlotte Mary Yonge. She called la Motte Fouque “one of the foremost of the minstrels or tale-tellers of the realm of spiritual chivalry.” la Motte Fouque read in a way sure to please the following century’s C. S. Lewis, according to Yonge: “…he saw Christ unconsciously shown in Baldur, and Satan in Loki.”13

Yonge’s inclusion of the tale of Sintram in The Heir of Redclyffe inspires Jo to read Sintram for herself:

“I do want to buy Undine and Sintram for myself; I’ve wanted it so long,” said Jo, who was a bookworm.14

Similarly, “book-worm”15 is applied to Guy, albeit in disbelief, for Guy (like Laurie) does not love to study, though he disciplines himself. Guy loves the story of Sintram, and an illustration of Sintram drawn by Laura, because it encourages him that he can conquer his tumultuous feelings. Jo must have felt a kinship with Guy given her tendency to anger, and the encouragement Guy found in Sintram perhaps encouraged Jo that she, too, could learn from Sintram’s “spiritual chivalry.”

“Little Tripping Maids May Follow God:” Alcott and Yonge

Of the early signs of Jo’s book-love in Little Women, we have The Heir of Redclyffe, Sintram, Pilgrim’s Progress, and the Bible.16 Yonge wrote one, endorsed another, knew the third, and devoted her life to the fourth. Alcott and Yonge lived quite different lives, Yonge in England and Alcott in the United States. Alcott’s parents were radical activists who provided an unstable living situation for much of her childhood. Yonge had comparative wealth and stability, and was at ease with the social patterns of her day. Alcott was influenced by her father and neighbors, leading Transcendental minds, while Yonge was influenced by her neighbor and priest, a leading Tractarian. Yet, neither woman married, both were dedicated to their parents, and both penned bestselling, enjoyable family stories with characters who seek moral improvement and make goodness attractive.

In the preface to Little Women, Alcott adapts lines from John Bunyan:

Go then, my little Book, and show to all That entertain and bid thee welcome shall, What thou dost keep close shut up in thy breast; And wish what thou dost show them may be blest To them for good, may make them choose to be Pilgrims better, by far, than thee or me. Tell them of Mercy; she is one Who early hath her pilgrimage begun. Yea, let young damsels learn of her to prize The world which is to come, and so be wise; For little tripping maids may follow God Along the ways which saintly feet have trod.

Alcott’s epigraphical hope for her work is mirrored in Yonge’s, who wrote with “Confirmation girls” in mind.17 Despite their (not inconsiderable) differences, Yonge and Alcott write similarly.18 Yonge influenced Alcott to the point of Alcott choosing Yonge’s novel as an influence for her fictional aspiring writer. For Jo, Yonge’s “little book” told her “of Mercy,” as la Motte Fouque’s Sintram ministered mercy to Guy. Alcott’s hope for Little Women is accomplished in its readers: in reading her work, young damsels have learned to prize the world which is to come. I know this, for I am one.

Alcott’s popularity has eclipsed Yonge’s in the long run,19 but Alcott’s perpetual appeal should encourage us to look into her inspirations and sources.20 Alcott’s and Yonge’s mutual themes of moral improvement, and Yonge’s theme of spiritual refinement, are especially appropriate reading for the season of Lent. To those like me who grew up reading Alcott, and to anyone still growing up who counts herself an honorary March girl, I encourage you to give Yonge a try. (And I defy you not to weep a little weep where Jo did in The Heir of Redclyffe. You’ll know the spot.)

For Further Reading

The Annotated Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, edited by John Matteson (2015)

The Heir of Redclyffe by Charlotte Mary Yonge (1853)

The Daisy Chain by Charlotte Mary Yonge (1855)

Charlotte Mary Yonge: The Story of an Uneventful Life by Georgina Battiscombe (1943)

Charlotte Mary Yonge: Writing the Victorian Age, edited by Clare Walker Gore, Clemence Schultze, and Julia Courtney (2022)

Little Women, chapter 3. “Meg found her sister eating apples and crying over the Heir of Redclyffe, wrapped up in a comforter on an old three-legged sofa by the sunny window.” I won’t be citing page numbers since different editions abound and the full text is searchable online: Little Women at Project Gutenberg.

Charlotte Mary Yonge: The Story of an Uneventful Life by Georgina Battiscombe (1943), 57. The full text is available on Internet Archive. Battiscombe found resonance with Yonge during the Second World War: “whilst empires crumble and nations stand afraid, dear Miss Yonge remains a comforter.” (165-170)

This movement was called Tractarianism after Tracts of the Times, a series of theological writings by Keble, John Henry Newman (who converted to Roman Catholicism and became a cardinal), Edward Bouverie Pusey, and others. Keble College, Oxford, is named after John Keble. Yonge employs epigraphs in her chapters and Keble supplies several; Guy receives a Christian Year in chapter 6. Keble enjoyed Yonge’s novels and continued reading them in his old age. John Keble: A Study in Limitations by Georgina Battiscombe (1963), 344.

Anne Boyd Rioux, Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters, 49. Rioux also misplaces Jo’s reading of the book in chapter 2, when it occurs in chapter 3.

“I like good strong words that mean something,” says Jo in chapter 4 of Little Women.

“‘She made goodness attractive’ was said of [Yonge] in her capacity as a novelist by, I think, Mrs. Romanes [Yonge’s first biographer].” E. M. Delafield, “Introduction,” in Charlotte Mary Yonge by Georgina Battiscombe, 13.

E. M. Delafield in Battiscombe, 14. Delafield also gives us this gem: “Art is long and Time is fleeting, and paper, at this date, is rationed.” (15)

The Heir of Redclyffe, chapter 3. I won’t be citing page numbers since the full text is searchable online: The Heir of Redclyffe at Project Gutenberg. Yonge must have enjoyed dogs, for she describes Guy’s dog Bustle, a spaniel, before likening Guy to a greyhound: “A large beautiful spaniel, with a long silky black and white coat, jetty curled ears, tan spots above his intelligent eyes, and tan legs, fringed with silken waves of hair.” The Heir of Redclyffe, chapter 2.

Little Women chapter 39, “Lazy Laurence.”

Illness unspecified, but he can walk with crutches and suffers from debilitating bouts of pain.

Faber-Castell still makes quality art supplies today.

The Heir of Redclyffe, chapter 5.

“He lived in a continual glamour of spiritual romance, bathing everything, from the old deities of the Valhalla down to the champions of German liberation, in an ideal glow of purity and nobleness, earnestly Christian throughout, even in his dealings with Northern mythology, for he saw Christ unconsciously shown in Baldur, and Satan in Loki.” Yonge’s introduction to Sintram and His Companions: And Undine. In Surprised by Joy, Lewis reads “Balder the beautiful / Is dead, is dead.” This is one of the three experiences, alongside Warnie’s toy garden and Squirrel Nutkin (the “Idea of Autumn”), that encompass “the central story of [his] life.” Surprised by Joy, Harvest, 1955 (17).

Little Women, chapter 1.

The Heir of Redclyffe, chapter 5.

At the beginning of chapter 2, the March girls receive “guidebooks” in colors matching their characters. John Matteson notes that there is debate regarding whether these books are Pilgrim’s Progress or Bibles. He decides that they are Scripture, based on the discovery of Lizzie Alcott’s New Testament at Orchard House. The Annotated Little Women, ed. John Matteson, 22.

Yonge was the first editor of The Monthly Packet, a magazine for adolescent Church of England girls. Volume III (Parts XIII-XVIII, January-June 1892) is available online.

Charlotte Mitchell notes that Yonge’s The Daisy Chain (1856) was “an important model for Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women….Invalidism, the nature of true gentility, the heroine’s impatience with the restrictions of young ladyhood, the contrast between the poor and well-born and the rich and vulgar, the necessity of holding a high religious ideal before one—all these themes echo preoccupations of Yonge to the point where one feels confident that the teenage Alcott had read The Daisy Chain as enthusiastically as Jo March lies on the sofa weeping over The Heir of Redclyffe.” Mitchell also connects Guy and Laurie, and Jo’s longing for Sintram with its presence in the novel. Anglican Women Novelists, ed. Judith Maltby and Alison Shell, 67.

“Emily Brontë, Dickens, Thackeray, even George Eliot, transcending the limitations of their setting, belong to all time, not to their times alone, but Charlotte Yonge is essentially Victorian.” Charlotte Mary Yonge by Georgina Battiscombe, 17.

I dearly hope the trend of scholarship about our favorite authors’ sources continues for many years. See Tolkien’s Modern Reading by Holly Ordway, What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (And Why) by Susan Allan Ford, and Jane Austen’s Bookshelf by Rebecca Romney.

So much good research and depth here, Melody! I need to revisit Heir of Redclyffe and try out some more CMY! I read it four years ago with a book group, but my memory is hazy now. I'm sending this to my sister who loves Yonge's novel and Little Women!

This was very interesting! I love learning about the books that influenced books I have read.