It’s May, a busy month of the year for life transitions. Graduations and parties and Memorial Day and weddings and festivities and remembrances abound. For those of us not in the limelight, sometimes it can feel like life is passing us by at these bittersweet moments. After we rejoice wholeheartedly at others’ opportunities, we return, both full and empty, to our humdrum lives. This is where Maud Hart Lovelace begins Emily of Deep Valley, the weekend of Decoration Day (now Memorial Day), when Emily is graduating high school and watching her friends leave for college, while she stays behind. It seems like life is passing her by.

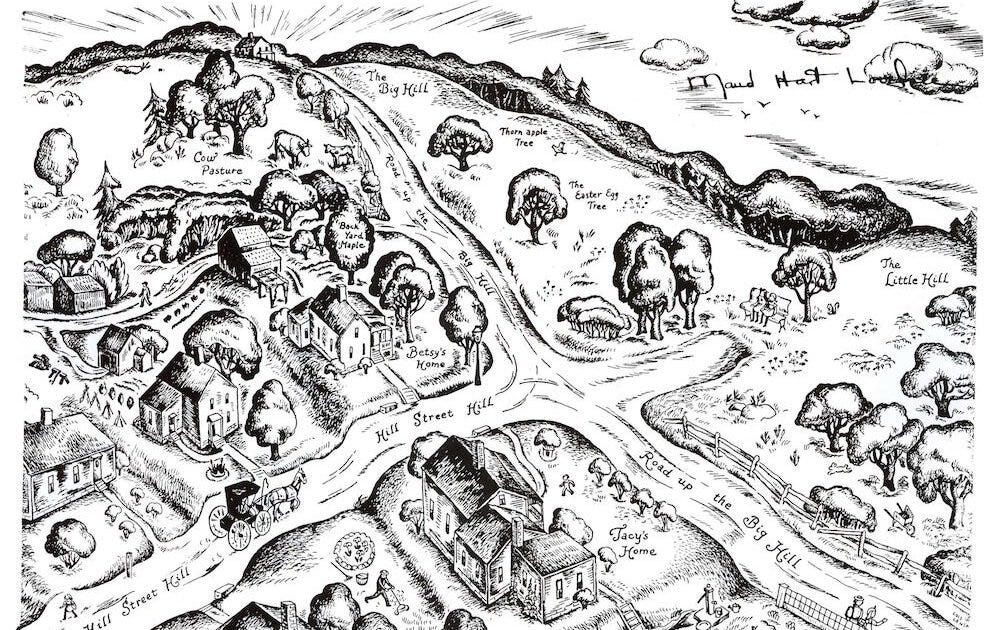

You might know Maud Hart Lovelace (1892-1980) through her effervescent heroine, Betsy Ray, of the Betsy-Tacy books. Lovelace takes her autobiographical heroine from age 5 to marriage, growing up in 1900s Minnesota (complete with a trip to Europe in 1913-1914).1 Lovelace also wrote short stories and historical fiction, but her Deep Valley works are set in a fictionalized2 version of her Minnesota home of Mankato. The Deep Valley books have endured in the hearts of readers since the 1940s, from Bette Middler to Ann M. Martin to Mitali Perkins.

In her foreword to Emily of Deep Valley, Perkins writes, “Yes, Emily had many likeable character traits, but unlike Betsy, she isn’t best friend material at all. Why not, you might be wondering? Well, because Emily is me.”3 Betsy’s stories are full of friendships, hijinks, dances, and dreams. Who doesn’t want to be Betsy’s best friend? Her musical older sister Julia, Mr. Ray’s onion sandwiches, and the happy bustle of the Ray household make her home as attractive as any. Emily, on the other hand, lives alone with her grandfather on the outskirts of town. There’s no telephone ringing with dance invitations, nor a crowd of friends in the kitchen on Sunday nights. Emily of Deep Valley takes us to a quiet home and its quiet heroine, Emily Webster.

Commencement and Remembrance

Emily Webster, based on Lovelace’s friend Marguerite Marsh,4 is an orphan who lives with her grandfather in an old house near the slough.5 After her grandmother’s passing, Emily is steadfastly devoted to her grandfather. She won’t countenance leaving him with a housekeeper while she goes to college. As profoundly as she longs for higher education, Emily is unshaken in her commitment to care for her grandfather in his old age. Cy Webster does not hold his granddaughter back, and encourages her social life and all her schemes, but in his age and growing feebleness, he can do little for her on his own.

While her peers seem to advance footloose and fancy-free into their futures, Emily starts the morning of her senior Class Day by clearing and decorating the family graves for Decoration Day, now known as Memorial Day. Her grandfather fought at Gettysburg with the First Minnesota, and he and the few living Civil War veterans march in the annual parade. Unlike her friend who finds Decoration Day “bunk,” Emily finds the “young men of the First Minnesota who had charged so bravely to their death…almost as real to her as last year’s football team.” (54) Having been raised by her grandparents, Emily’s sense of the past is stronger than her peers’, and she learns over the course of the book what a gift that is.

Eager Young Lads and Roués and Cads

Emily was the only girl on Deep Valley High School’s star debating team. She gave an oration on Jane Addams at her high school graduation. Yet, “she had never learned to joke and flirt with boys. Or perhaps boys just didn’t flirt with a girl who lived with her grandfather in a funny old house across the slough.” (5) Emily is left out of parties and dances because of her quiet, serious personality, and faces rejection even when forcibly included by well-meaning girl friends.

Despite knowing her social shortcomings, Emily has a long-held, unrequited crush on Don Walker from her debating team. Emily is awed by Don’s intellect, but the canny reader sees that Don is brash but unformed. He is wrapped in self-deception, disdaining today what he praised yesterday. He teases Emily with “familiar insults” (79) for her ideals and favorite poetry. When he visits her—only while “everyone else” is out of town—he has “an air of lordly condescension.” (80-81) In Emily’s small circle of peers, Don is the smartest, one of the few willing to talk with her about the politics6 and literature she loves. Don represents to Emily the dreams she forfeits, and their relationship is always tinged with Emily’s pain.

When Emily finally decides to stop wishing her high school days back, she puts her hair up and joins the adult world herself. In the Deep Valley literary universe, Emily is a few years behind Betsy, and Betsy’s friends seem impossibly adult to Emily, but once Emily puts her hair up, they stop seeing her as a high school kid. Lovelace takes us back to Betsy’s crowd, with Cab Edwards taking a brotherly interest in Emily’s social life. Cab left high school when his father died so he could provide for his mother and siblings. Out with Cab and his friends, and Emily sees that staying behind in Deep Valley need not mean mouldering in her own low feelings.

“Muster Your Wits”

With all her friends away at college and corresponding less than she hoped, Emily feels “lonely and deserted and futile. ‘A mood like this has to be fought. It’s like an enemy with a gun,’ she told herself. But she couldn’t seem to find a gun with which to fight.” (102) College had been Emily’s only vision of the good life, but her conversation with Cab invites her to recast that vision. Emily has the resources within and around herself to live a fulfilling life.7 Soon after, Emily’s pastor quotes Love’s Labor’s Lost8 in a sermon:

Encounters mounted are Against your peace. Love doth approach, disguised, Armèd in arguments. You’ll be surprised. Muster your wits, stand in your own defense, Or hide your heads like cowards, and fly hence.

“Muster your wits, stand in your own defense,” Emily repeats to herself as she goes home. “I’m going to fill my winter and I’m going to fill it with something worth while.” (129) Emily looks around her for resources: reading Sir Walter Scott and a biography of Abraham Lincoln to her grandfather; starting a Robert Browning reading group; and finding her own meaningful work right in Deep Valley.

Through a purchase of frogs’ legs, Emily and her grandfather befriend young boys from the local Syrian refugee settlement. (Readers of Betsy and Tacy Go Over the Big Hill will remember visits to the neighborhood called Little Syria.) Emily receives hospitality from Kalil, Yusef, Layla, and their families. She learns about their celebrations on Christmas Eve (the Night of the Birth), and welcomes the children into her own home for an American Christmas celebration on Christmas Day. Here, she and her grandfather discover that the children are being bullied by their classmates for their ethnicity. Together, they start a club for the children to help them hone their English skills and develop cross-cultural relationships in a safe place.9

Emily becomes so invested in the Syrian refugee community that she works up a project to start citizenship10 classes at the local high school, taught by enthusiastic faculty. Her graduation oration on Jane Addams finds its fruit in her advocacy. It’s Emily’s heartfelt plea that convinces the school board to approve citizenship classes for the Syrian community. Emily had dreamed of studying social work at college, but when she finds that there is a need in her own backyard, she answers it.

To Fly in the Greatness of God

As a child, I thought Maud Hart Lovelace the most romantic author name imaginable. I thought it must have been a nom de plume, but it is her real name (her birth name was Maud Palmer Hart). Lovelace lives up to her name and laces Emily’s life with a romantic love, but you’ll have to read the novel to follow the slow blossom of her affection.

One summer day, Emily quotes Sydney Lanier’s poem “The Marshes of Glynn” to Don:

As the marsh-hen secretly builds on the watery sod, Behold I will build me a nest on the greatness of God: I will fly in the greatness of God as the marsh-hen flies...

Emily finds resonance in this poem with her own beloved slough, though Don scorns her interpretation. Don looks for intellectual challenge and aesthetic pleasure beyond Deep Valley. For a while, Emily despairs of finding it in Deep Valley, too.

Then, like Lanier’s marsh-hen, Emily musters her wits. She “secretly builds.” She is hidden from the world outside Deep Valley, and her languishing high school friendships make her feel unseen. In Lanier’s poem, “the greatness of God” is found within the greatness of the marshes.11 When she musters her wits, Emily finds happiness not by despairing over her future or longing to be somewhere else, but by putting down roots right where she’s lived all her life: “By so many roots as the marsh-grass sends in the sod / I will heartily lay me a-hold on the greatness of God.”12 Emily learns to love where she lives, to find problems in her own town that she can help solve, and learns to “fly in the greatness of God.”

Decades after Emily of Deep Valley was published, Cass Elliot would sing, “don't let the good life pass you by.” When Emily was passive, watching life pass her by—literally, by sending her friends off to college on the train platform—she fell into despair. When Emily mustered her wits, and actively stood in her own defense, she found the good life right where she was. Her slough was not one of despond, but of joy. Like Emily, we can take Cass Elliot’s practical advice, too: help a neighbor, have a cry, hold a hand to stop its trembling, watch a child pray. We can muster our wits and stand in our own defense. As Lanier witnessed, we can build our nests secretly on the marshes. We, too, can find the greatness of God in the slough, and fly in it.

For Further Reading

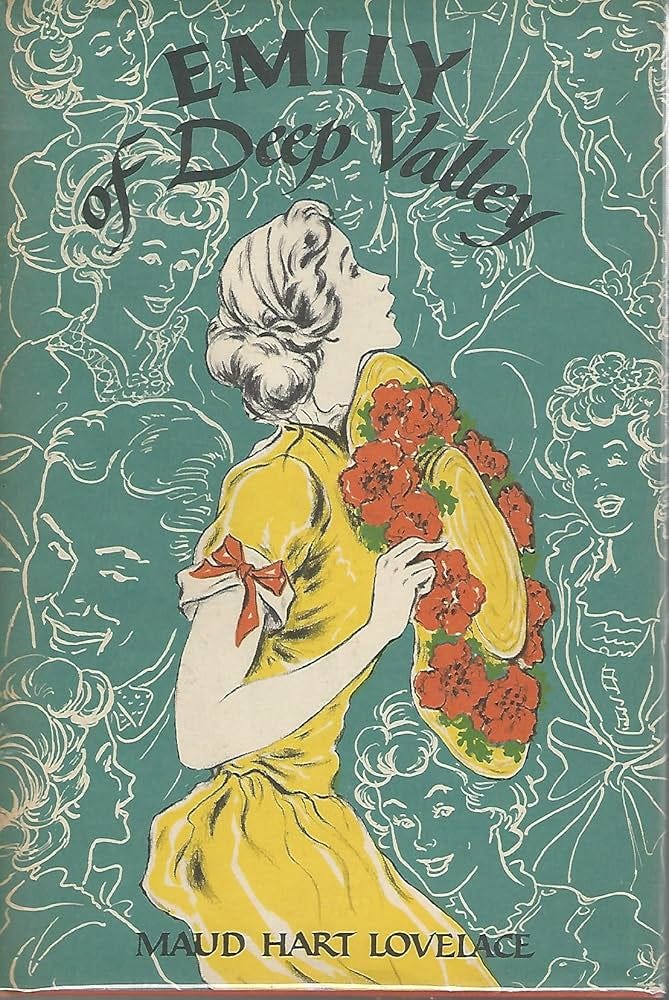

Emily of Deep Valley by Maud Hart Lovelace

Steeped in Stories: Timeless Children’s Novels to Refresh Our Tired Souls by Mitali Perkins

The Betsy-Tacy Companion by Sharla Scannell Whalen (out of print)

Online Resources

Lovelace Family Papers at Minnesota Historical Society

Betsy and the Great World (1952) concludes with Betsy leaving England just after the Great War is declared.

While Lovelace idealized and fictionalized her home, Sharla Scannell Whalen’s The Besty-Tacy Companion finds as much fact as fiction in the Betsy-Tacy books.

Foreword by Mitali Perkins, Emily of Deep Valley, viii (HarperCollins, 2010).

See the 2010 edition of Emily of Deep Valley for a biographical note about Marguerite Marsh.

Lovelace had Emily read the same books we do: “The Deep Valley slough, pronounced sloo, was the marshy inlet of a river. When Emily had first read Pilgrim’s Progress, after finding it mentioned in Louisa M. Alcott’s Little Women, she had pronounced the Slough of Despond sloo, too. She had called it sloo until Miss Fowler had told her in English class that Bunyan’s Slough rhymed with ‘how….’ The difference in pronunciation had seemed suitable to Emily. Slough pronounced like “how” sounded disagreeable, and so did the miry pit in which Christian had wallowed. She loved her own slough, pronounced sloo, beside which she had lived all her life.” Emily of Deep Valley, 15-16.

Emily of Deep Valley is set during the tumultuous presidential race of 1912, when Teddy Roosevelt lost the Republican nomination to William Howard Taft and formed the Bull Moose Party.

In Betsy’s story arc, Lovelace doesn’t write much about the year Betsy spends living with her grandmother in California during her “lost year” (the year before she goes to Europe). We don’t get a hearty picture of Betsy at college like we do with her high school years. Lovelace seems to have a reticence to write about Betsy’s depression directly, instead showing Betsy to her readers before and after that year. Emily of Deep Valley explores the idea of a “lost year” becoming a found year: “That ‘lost year’ gave me a chance to do some thinking. I got acquainted with myself, I found myself, out there in California…I wanted to write before, and I still want to write. But I changed…It did me good to get away from my friends.” Emily of Deep Valley, 206-207.

Act 5, Scene II, lines 88-92, spoken by Boyet to the Ladies.

A safe place, that is, which involves wrestling! The challenge for Emily is in the (lack of) eagerness from people in her culture to welcome those from a different culture. Mitali Perkins’s introduction, and her splendid chapter on Emily in Steeped in Stories, explores this aspect of the novel. Perkins met Emily as an “immigrant reader on the fire escape” in New York City, and she interprets the story through the lens of “Despair and Hope.” Steeped in Stories, 87-105.

They are called “Americanization” classes in the novel, but “The idea is to help new arrivals to adjust themselves and to prepare them for the examinations they are required to pass before they can be admitted to citizenship.” Emily of Deep Valley, 254. The classes cover the English language, US history, and US government. Emily never shows a desire to erase or change the Syrians’ culture, but only to increase the ease of their living in the US by teaching the adult women English and providing classes for all adults to prepare for citizenship exams.

“like to the greatness of God is the greatness within / The range of the marshes.” “The Marshes of Glynn.”

Perhaps the dilemmas faced by the main character is similar to those of us who grow up in simple places without a guided future or the means to create the one that would seem to fulfill our dreams. Then the lesson of the story becomes that the way to find contentment is to at some point accept our lot in life and embrace the opportunities found therein ... a valuable lesson to learn sooner rather than not at all; and be forever frustrated.

Thanks again for sharing!

I must read this book forthwith! I hadn't heard of it before today but I'm beginning to think Emily must be one of the race that knows Joseph.