Despite their grisly connotations, I find mystery novels comforting. The culprit is caught, justice is served, and the victim (however disliked) is vindicated. We shall all die, mystery novels remind us, but they also remind us that thou shalt not murder. If only real life was so straightforward.

The Golden Age of mystery novels spanned the 1920s and 1930s, a time of significant social upheaval. After the Great War, called the “war to end all wars,” young people redefined their place in society. Europe took years to recover financially and socially after trench warfare. A global financial depression created social unease that contributed to rising powers of communism and Nazism. The future was murky. Building off the relatively new concept of the mystery novel,1 authors set forth to create worlds where justice was hard-won but possible, where intricate mysteries unraveled before a keen detective’s mind.

Golden Age authors like Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers were at peak production in this period. In the midst of this literary movement, the Detection Club was founded.2 A highly selective group of mystery novelists, including G. K. Chesterton (the first president), Christie, Sayers, and Baroness Emma Orczy, gathered to share their ideas and improve each other’s writing. The novelists agreed to adhere to a set of rules3 to give their readers the chance to figure out whodunit.

Into this world of crime and punishment came the novels of E. C. R. Lorac, who began publishing in 1931. Lorac’s Chief Inspector Robert Macdonald solved crimes by wits alone, no intuition, just good plain detecting. While Lorac sometimes plumbed London’s crime scene and English prisons for inspiration, usually respectable members of society peopled the pages. Though Lorac published continually for nearly thirty years, the publishing industry is not an infrequent complication in these mysteries.

Life of an Author

E. C. R. Lorac was a nom de plume of Edith Caroline Rivett (1894-1958). She went by Carol Rivett for most of her life, and published under the names of E. C. R. Lorac (her initials and her nickname backwards), Carol Carnac, Mary Le Bourne (very close to Marylebone, a parish now in London), and Carol Rivett. Relatively little is known about her life, and few pictures of her exist. What we do have are dozens of excellent mystery novels that earned Lorac an invitation to join the prestigious Detection Club.

Lorac spent her final years living in Aughton, Lancashire, with her sister Gladys. Besides writing, Lorac studied art and design, likely creating the richly embroidered tunicle she donated to Westminster Abbey.4 Her beloved Lancashire figured into several of her mysteries, and is the longed-for home of her Scottish detective Robert Macdonald.

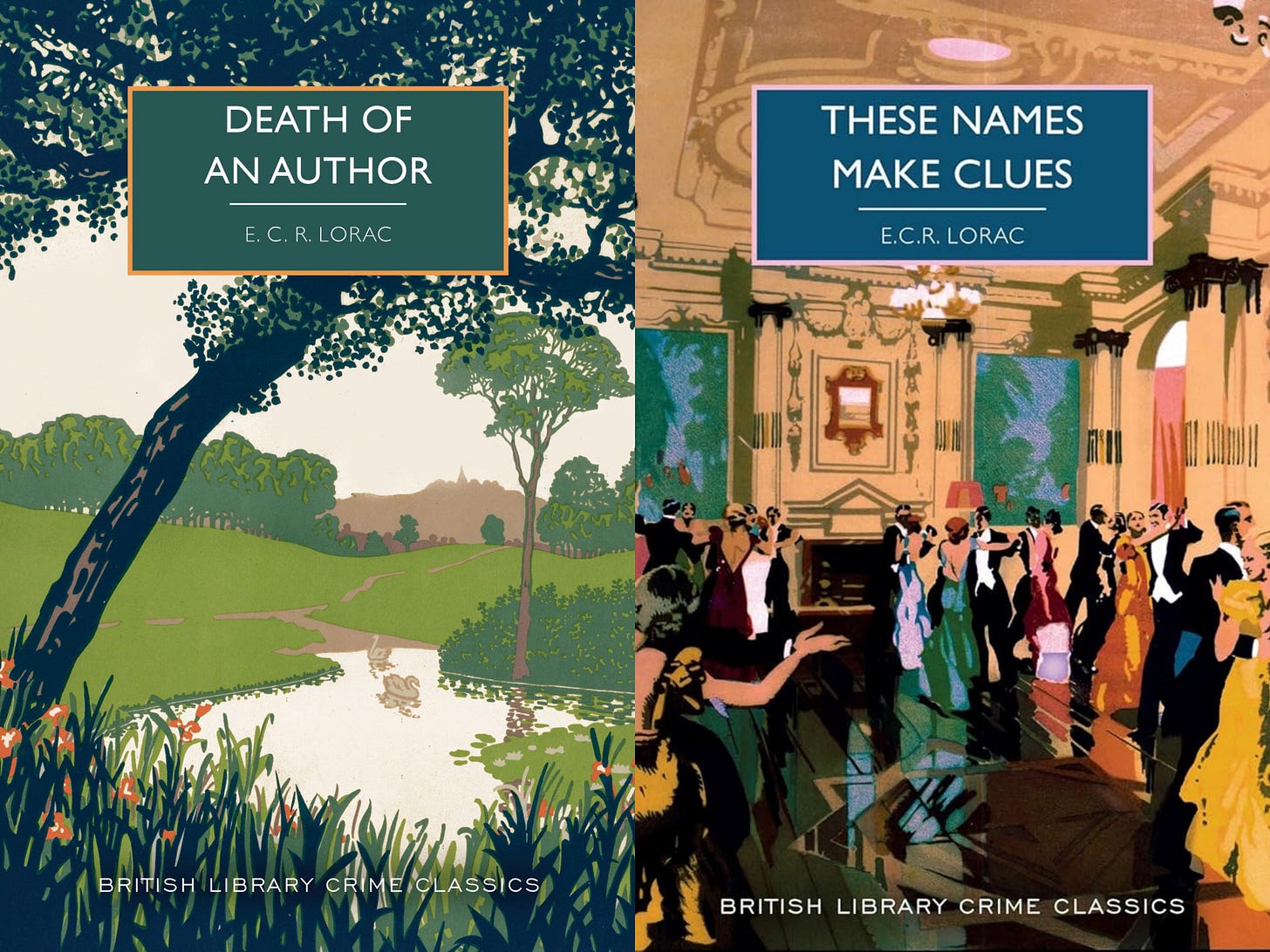

Women and Mystery

Today, we know mystery novels are a field where women writers reign as easily as men. The bestselling author of all time is Agatha Christie, after all.5 Yet, in Lorac’s day, Christie and Sayers had not quite broken the glass ceiling. Lorac chose an ambiguous name to tease her audience. Could one solve the mystery of the author’s sex from the text alone? Lorac plays with this in Death of an Author (1935),6 a mystery concerning an author and a secretary—or are they one and the same?

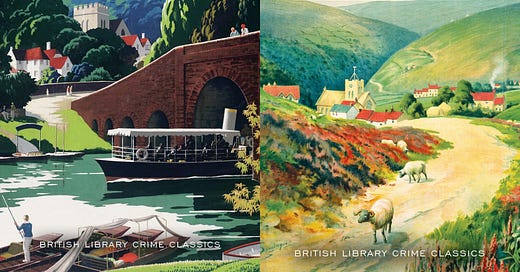

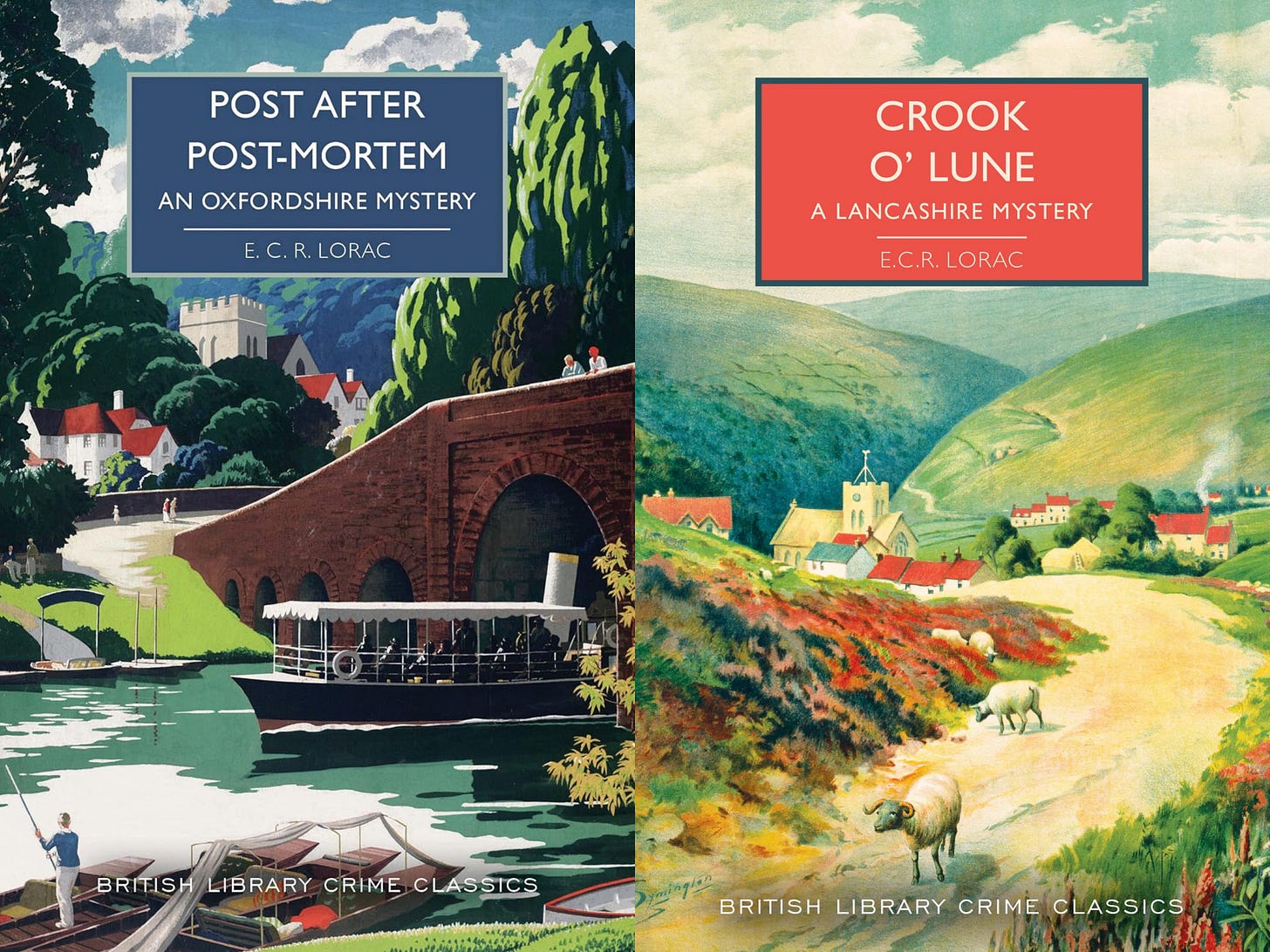

Post after Post-Mortem (1936) plumbs the secrets of a writing family, when one of their scribblers dies in the middle of a house party at which the publisher and other authors are in attendance. While Lorac enjoyed strong sales and often published several novels in the same year, she changed publishers once her works began to receive acclaim—did this inspire her to write about publishing squabbles? She skewers perceptions of novelists in These Names Make Clues (1937). A murder occurs at a party to which a variety of authors have been invited under pseudonyms like Fanny Burney, Jane Austen, Izaak Walton, and Laurence Sterne, based on their writings and personalities.

One of Lorac’s signatures, through her character Robert Macdonald, is honoring the everyman. Macdonald is polite to everyone, from the pub cook who provides his lunch to a worker at a train station. Of course, his graciousness helps him when he needs eyewitnesses and clues, but one can’t help but feel that Lorac’s Scottish detective lacks the snobbery common to the upper class of his day. Lorac takes a special interest in single women making their own way in life, not belittling them or marrying them off, but showing them living happy independent lives (until, that is, they or someone they know is murdered).

Lorac is one of the deserving authors being retrieved for contemporary readers by British Library Crime Classics, published in the United States by Poisoned Pen Press. I would recommend reading Martin Edwards’ introductions after completing the novels, as the mystery is often spoiled, but in them he provides a lively glimpse into Lorac’s world. Christie’s well-deserved popularity has kept Hercule Poirot and Miss Jane Marple in public memory, but Christie worked with the Detection Club to encourage other mystery writers, too. They flourished when collaborating with each other, and the Detection Club even published several story collections together. As Lorac’s work is brought once more to the reading public, she is making a second splash.

Conclusion

As an avid reader of mystery novels, when I started reading Lorac she quickly became a favorite. I enjoy her settings, whether it’s a beautiful old house in the English countryside or a locked apartment in London. Her characters, though not as deeply explored as those of Sayers or Christie, are vivid. Lorac’s use of publishing drama and bibliophilic clues are a constant source of delight. I would become CI Macdonald’s housekeeper in Lunedale (Crook o’ Lune, 1953) in a heartbeat.

If you already enjoy the novels of Christie, Sayers, and their co-conspirators, you will likely enjoy Lorac. In all the novels of hers I’ve read, I found myself deeply invested, and enjoyed turning over the clues in my mind. A little detection of your own and you can solve the mystery, per Detection Club rules, and enjoy a trip to Lorac’s England along the way.

Significant early mystery novels and novelists include Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, which has been called the first major detective novel, the works of Wilkie Collins, and novels about a certain character written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

See The Golden Age of Murder: The Mystery of the Writers Who Invented the Modern Detective Story by Martin Edwards (2015) for a riveting account of the Detection Club and its members. Dorothy Sayers scripted eerie rituals, the authors co-wrote detective stories, and they even had a human skull as mascot.

Ronald Knox’s Ten Commandments, which include ruling out supernatural agencies, having no more than one secret passage/room, and no surprise identical twins. Knox came from the famous Knox family, including his father Edmund (bishop of Manchester) and his siblings Winifred Peck (author and novelist), Alfred (Bletchley codebreaker), Edmund (satirist, editor of Punch), and Wilfred (scholar and priest). Ronald distinguished himself in the family not only by his writing, but also by converting to Roman Catholicism and becoming a priest in both the Anglican and Roman Catholic traditions.

“Vestments and Frontals,” Westminster Abbey.

This claim is made by her estate. Christie holds the Guinness World Record for Most Translated Author.

Yes, Death of an Author predates “The Death of the Author” by Roland Barthes by a few decades.

No wonder you and your other half enjoy Escape Rooms. Tis the mystery in you, my dear! Nicely done!

That picture of the Detection Club is priceless! I love that you wrote about Lorac. She has been my favorite mystery writer discovery to date. (I'm quite new to the genre minus The Boxcar Children!) Gracious is the perfect desciptive term for Macdonald. He's up there for me with Lord Peter and Miss Marple. He takes a while to grow on one, but the more I read his character, the more vivid he becomes. I'll gladly join the household as cook or housemaid!