In my work as a historian, I encounter many creative, intelligent people from the past who hold views contrary to mine. From flat-earth theory (not in an ironic way) to rabid proslavery, there’s a lot of bad in with the good. How should we discern who receives our time and attention? Wouldn’t we be better off reading Frances Ellen Watkins Harper rather than Rudyard Kipling? Yet, Harper’s mighty words lack their impact outside of her context, a world that was cold and cruel toward Black women. Nor can we deny that the legacy of Kipling’s waltz with the English language is still felt today.

In An Experiment in Criticism, C. S. Lewis writes:

…A true lover of literature should be in one way like an honest examiner, who is prepared to give the highest marks to the telling, felicitous and well-documented exposition of views he dissents from or even abominates.1

We cannot fully separate the art from the artist. Does not all art lose its meaning when stripped of its time, place, and body? Even the anonymous artist lives in our minds. Yet, we can discern between the artistry and content of a work, and the virtue of the artist.

Judged by What Standard?

We must learn the language of the past, unique to each place and time. There was a time before cars were common, which meant horse droppings littered the sides of every road, a detail avoided by the refined cameras of most period dramas. Before sunscreen, our wise ancestors wore yards of fabric in the summer, which we imagine might have been hot and constrictive, even though it wasn’t. Yet, we don’t ridicule Around the World in Eighty Days because Phileas Fogg didn’t use transatlantic air travel, and instead marvel at Nellie Bly’s seventy-two day record.

When we refer to judging by modern standards, we’re usually not talking about advances of science and technology that people in the past did not have. We’re talking about social mores and evolving views on human rights. Some say we should make allowances for popular, if bigoted, views of the past, because “they didn’t know better.”2 Alan Jacobs has a different take:

…we should judge characters from the past in precisely the same way we judge characters of our own time, according to whether we think their behavior is good or bad, virtuous or vicious. (The viewer [of The Taming of the Shrew] who calls Petruchio’s treatment of Kate abusive is not wrong. The reader who says that [David] Hume was straightforwardly racist is not wrong.)…We need to look at the whole person, and if we do our task becomes more complex, but also more rewarding.3

Consider the Founders of the United States, many of whom were slaveholders. “It seems to me,” Jacobs says, “that what we ought to say about [the Founders of the United States] is that they rarely understood the full implications of their best ideas.”4 Thomas Jefferson wrote, “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”5 Jefferson, who enslaved people, did not believe in the highest implication of his idea. Ideas have consequences, and they outlive their creators. Jefferson’s idea spread to the Massachusetts state constitution, which inspired Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman to sue the state for her freedom and win. Jefferson’s own idea contributed to the legal foundation for the end of slavery in the United States. If we toss out Jefferson’s idea because he failed to live up to it, we fail those who did live up to it.

What About Original Intent?

Madeleine L’Engle writes about art as a work that must be served. To create good art is to obey the work that must be brought forth, or risk releasing a poor creation into the world. Serving the work, instead of the ego of the artist, is what invites the audience to interpret a larger meaning. She writes,

When a shoddy novel is published the writer is rejecting the obedient response, taking the easy way out. But when the words mean even more than the writer knew they meant, then the writer has been listening. And sometimes when we listen, we are led into places we do not expect, into adventures we do not always understand.6

Interpreting a work in its original context is important. Without that, we lose much of the meaning and the details that make the work come alive to us. Beginning and ending with original context, however, can lead to wooden interpretations. A lively interpretation involves our whole selves, our experiences and ideas, modern though they be. Few artists explicitly interpret their works for us. Great artists expect their works to stand on their own merits. Artists who have faithfully served their works also trust their audiences to interpret. For good or ill, interpretation is an important part of engaging with art, and art interprets us as much as it interprets the artist to us.

When we engage with artists in their contexts, we will understand them better, which is an act of grace. Artists also create as an act of grace,7 giving us a work that we can creatively engage through interpretation. Sometimes, that means making a moral judgment on a display of vice, which should provoke us to choose virtue.

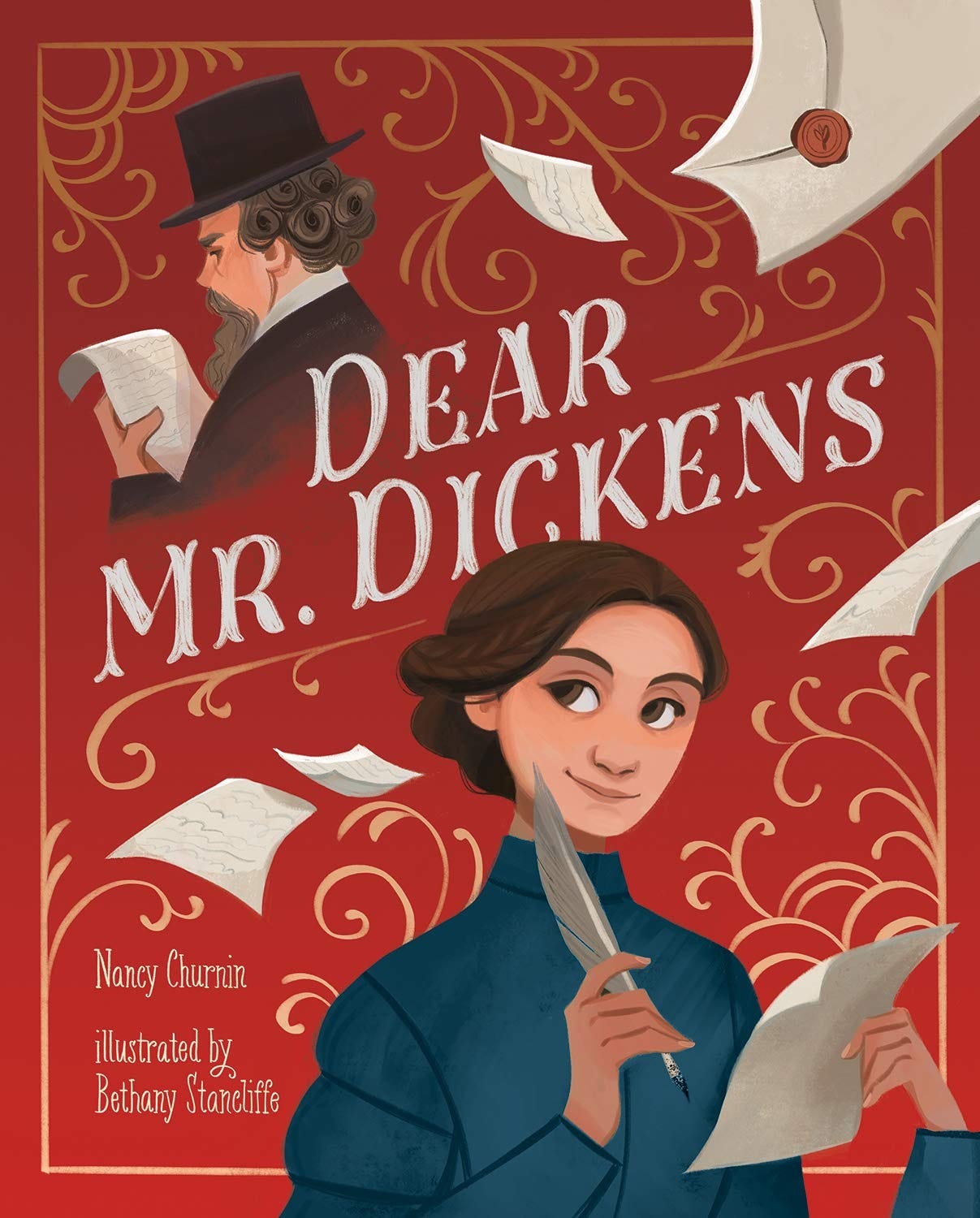

Righting a Wrong: The Case of Charles Dickens

Unlike artists in the past, who are alive to us through their work, artists who are still alive must answer for their actions. In the picture book Dear Mr. Dickens, Nancy Churnin tells the true story of Eliza Davis, an avid reader of Charles Dickens. Davis, a Jewish woman, was troubled by Dickens’s depiction of Fagin “the Jew,” an evil character in Oliver Twist. Dickens referred to Fagin as “the Jew” rather than by name, casting a dark shadow on the reputations of living Jewish people, who did not have equal rights in England for much of the nineteenth century. Instead of leading a boycott against Dickens’ work, Davis wrote to him directly, telling him that the way he wrote about Fagin demonstrated “a vile prejudice.” Dickens responded in denial, without courtesy, calling Davis over-sensitive. Clearly Davis’s words convicted Dickens, but he was not ready to change.

Davis mustered her courage and responded. Didn’t Sir Walter Scott write of noble Jewish characters? Though Dickens claimed that he wrote evil characters who were not Jewish, Davis noted that every Jewish Dickens character was evil, which did not “present Jewish people ‘as they really are.’” Davis thought of us, telling Dickens that he would be judged by future readers for his prejudice.

Dickens did not reply to Davis’s cogent arguments. Nearly thirty years after the publication of Oliver Twist, Dickens’s final completed novel began to appear in installments. Our Mutual Friend included a Jewish character, Mr. Riah. He protected the heroine, Lizzie Hexam, from assault. He stood up for what was right, for himself and others, even when the cost was high.

Mr. Riah was not all that Dickens did to atone: he used his platform to amplify those speaking out against prejudice. He changed the text of Oliver Twist in new printings to be less antisemitic, calling Fagin by name instead of “the Jew.” Davis wrote to Dickens one last time, giving him an English-Hebrew Bible, saying he had “‘the noblest quality a man can possess,’ the ability to atone.” Dickens’s final response thanked Davis for giving him the chance to do what was right.

Had Dickens died without atoning for his wrong, we would surely remember him differently. Clearly, he struggled to confess his wrongdoing, but once he decided to atone, the way was clear: writing a better Jewish character, printing essays against prejudice, and thanking Eliza Davis for her actions. This tale of righting a wrong lives vividly in Dear Mr. Dickens, which received the 2021 Children’s Picture Book Award from the Jewish Book Council.

A Way Forward

Like people in the past, we can use our words to curse others. Or we can speak up for what is right. To living artists, we can cordially reach out, offering a better way as Eliza Davis did, even to those like Dickens who will not change immediately. When speaking of artists in the past, we can tell the truth, acknowledging a gift for rhyme or chiaroscuro or argument, even as we confess their vices.

Speaking the truth can hurt for a time. It’s not pleasant to admit that David, the shepherd who wrote Psalm 23, became a rapist and murderer. Once Nathan’s parable convicted him, David did not shy from atoning for his wrong. He knew the power of confession. Psalm 51 testifies that confession did not crush David’s artistic spirit, but brought his art to new heights. Truth-telling strengthens our muscles of virtue until we can “rejoice in the truth” and not fear it, all the better to receive and create art.

For those of us who are artists, whether writers, painters, actors, or more, we can vow as L. M. Montgomery’s heroine Emily Starr did in her diary:

“Be merciful to the failures, Emily. Satirize wickedness if you must—but pity weakness,” [said Mr. Carpenter.]

He stalked off then, and called school in. I’ve felt wretched ever since and I won’t sleep to-night. But here and now I record this vow, most solemnly, in my diary, My pen shall heal, not hurt. And I write it in italics, Early Victorian or not, because I am tremendously in earnest.8

As we read complex works of the past, we should discern right and wrong. We extend grace by understanding history and the people who walked in it, as we hope people in the future do for us. Refusing to tell the truth about artists of the past and making excuses for their wrongdoing is just as vicious as ignoring the past completely.

Setting things in context involves nuance, and nuance is a hard task. It requires careful thinking, further research, and more words. Walking the middle way of nuance keeps us from the extremes of fanaticism for idols who can do no wrong, or narrow-mindedness that fearfully rejects art.

Creating art is a risk, and receiving art is a risk. Art brings us to the limits of ourselves: emotionally, intellectually, spiritually. At these limits, we glimpse the glorious and the terrible. Art can convict us, and show us transcendent beauty. Let us not fear art, either creation or encounter, but avidly seek the truth it offers.

For Further Reading

Alan Jacobs, Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Reader’s Guide to a More Tranquil Mind.

Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art.

Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination.

Mitali Perkins, Steeped in Stories: Timeless Children’s Novels to Refresh our Tired Souls.

Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt, Redeeming Vision: A Christian Guide to Looking at and Learning from Art.

An Experiment in Criticism, C. S. Lewis (85-86). “A Modest Proposal” by Jonathan Swift is a study of a bad idea, well-expressed.

Historical research shows that, for any given controversy, dissenters were present more often than not, even if they were few in number.

Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Reader’s Guide to a More Tranquil Mind, Alan Jacobs (51). Italics original.

Breaking Bread with the Dead (51-52).

The Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson (paragraph 2).

Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, Madeleine L’Engle (13).

“And this all-wellness underlies true art (Christian art) in all disciplines, an all-wellness that does not come to us because we are clever or virtuous but which is a gift of grace.” Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, Madeleine L’Engle (68). Emphasis original; “all-wellness” after Julian of Norwich.

Emily Climbs, L. M. Montgomery (chapter 2).

I agree with Amy - I had not heard the inspiring story of Dickens and Davis. I appreciate that Davis’ approach allowed for reflection and redemption … much harder to accomplish in our own toxic and polarized cancel culture.

A thoughtful essay and refreshing to read. I especially like your comment about Jefferson:

“If we toss out Jefferson’s idea because he failed to live up to it, we fail those who did live up to it.” I would further argue that we cannot toss out Jefferson himself or any of our founding fathers because they failed to completely embody the ideals they were striving for; can any of us claim to perfectly live by the principles or standards we desire?