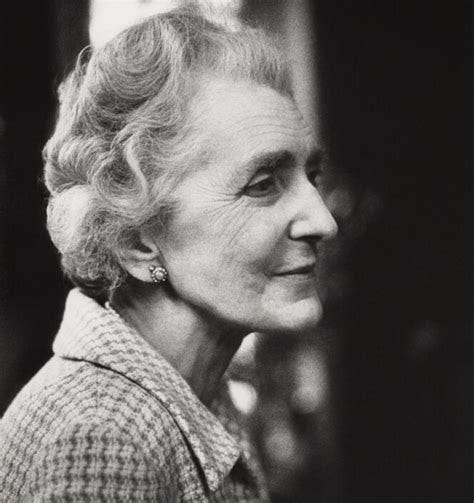

In the halls of literature, daughters of Anglican priests are well-represented: Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Noel Streatfeild are but a few of these sororal scribblers.1 Elizabeth Goudge (1900-1984) was born to an Anglican priest in Wells, England, near a cathedral where she set several of her novels. She had family roots in Guernsey, and lived for many years in Devon and Oxfordshire, setting novels in each place. She wrote delightful books for children and exquisite books for adults. Goudge lived a quiet life, caring for her parents until their deaths, and living privately in the country for the majority of her life. One might not expect deep insight into human nature from such a retired person, but like her fellow Anglican women novelists, Goudge’s keen insight into her characters shows a perspicacity only demonstrated by those who live hidden lives.

The Scent of Water (1963)

The Scent of Water2 tells the story of Mary Lindsay, a woman retiring from a long career in civil service. Mary inherits The Laurels, a house in Appleshaw in rural southern England. Instead of selling it, receiving her retirment pension, and living her familiar life in London, Mary feels drawn to move to The Laurels and restore the run-down house to itself. The Laurels was left to Mary by her father’s cousin,3 who sought the house for herself as a retreat, her final hope in a lifelong battle with an unnamed mental struggle.4 Mary knows suffering: “She had gone out to Germany with a Red Cross unit and worked with and for the shattered men and women coming out of the concentration camps. Nothing she had seen in the blitz had been more fearful.” (31)

Yet, “the noise, the rush, the luxury and the undercurrent of perpetual fear” (31) of postwar London was not where Mary chose to spend her retirement. In what felt like “an act of obedience” (26) Mary takes possession of The Laurels, and begins her journey through the stability of committing her life to this particular place.

The novel draws is title from Job 14:

For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease. Though the root thereof wax old in the earth, and the stock thereof die in the ground; yet through the scent of water it will bud, and bring forth boughs like a plant. Job 14:7-9 AKJV

The many characters in The Scent of Water have been “cut down,” with roots “waxing old.” Colonel and Mrs. Adams lost all but one of their sons in the war, and their remaining son is profligate. Paul Randall, a struggling writer, was blinded in the final weeks of the war, though his wife Valerie bears the bitterness. The Hepplewhites cannot tell the truth about themselves and their façades separate them from the rest of Appleshaw.

Goudge names her characters with great care. The Adamses, like the biblical Adam and Eve, suffer the loss of children and the knowledge that their remaining son lives “east of Eden.”5 Paul Randall is blind, like the Apostle Paul, but demonstrates an inner sight. Valerie, given the chance to rise to the occasion, shows not valor but pettiness. Hermione Hepplewhite’s journey at the end of The Scent of Water takes a Shakespearean turn, midwifed by Mary herself.

All of the characters are stunted in a way. All of them need springtime, a scent of water, to show forth a sprout again.

The Obstacles of Goudge

I’ve read a dozen of Goudge’s books by now, and her work occasionally troubles me. Several times, I’ve encountered racial slurs.6 It hurts my heart the way a character in The Scent of Water speaks about serving the local Romani families. Goudge’s casual references to child abuse in her adult novels has more than once punctured the joy I experience in reading her work.7 One of her early novels, The Middle Window, immortalized her temporary belief in reincarnation, which she later relinquished in favor of creedal orthodoxy.

I believe in telling the truth about artists, even the ones who are deceased, for artists live on in their work. We cannot expect any work of art, or any artist, to be impeccable. Do flaws not show us that the work was made by human hands?

Goudge, with her canny eye for human nature, would not expect us to treat her work with truth-eliding reverence. In The Scent of Water, even secret sins are revealed, and I doubt she would expect to have her own visible ones overlooked. Yet, Goudge’s appeal across generations shows that the goodness in her work is not erased by these glimpses of her human self. She was a human being: not always kind to others, sometimes saying the wrong thing, making errors of judgment. Who among us can call ourselves better?

Goudge did not place herself or her work on a pedestal. Realizing she had feet of clay was not shocking to me. Goudge thirsted for “living water”8 and steeped herself in worship, prayer, and spiritual reading. As a faithful Anglican, Goudge regularly confessed her sins, personally and corporately, in prayer. Her choices of prayers to anthologize in A Diary of Prayer show that Goudge felt the need to frequently confess her sin without being over-scrupulous. We need not struggle with the evidence of her imperfections. Her work teaches me to have a clearer vision toward my fellow humans, a loving gaze I can turn toward Goudge herself. The speck in her eye only makes the log in my eye more apparent to me. To speak the truth about these aspects of her work is to honor the edification I receive from reading Goudge, and to more fully receive her good gifts.

Learning the Spring by Heart

Telling the truth about one’s self is a mark of the characters in The Scent of Water who begin and end the novel at peace with themselves: Mrs. Croft, the midwife; the Bakers, a bodger and housekeeper; little Jeremy; and Mary herself, whose growth comes from responding to her cousin’s diaries, dealing with the loss of her long-ago fiancé, and restoring treasured objects to The Laurels.

The characters who begin the novel in self-deceit are the ones who undergo transformation. For most of them, it is quiet, an internal change that ripples out to the community. For some of them, it is drastic, or narrowly avoids being so. The titular “scent of water” is a motif for the persistence of hope in the face of fear:

The dew was heavy tonight, and most welcome in this dry spell. As always after working too hard [Paul’s] scarred face felt tight and hot, but the coolness of the dew and its faint scent eased him. The scent of water, of the rain and of the dew. It was difficult to separate it from the grateful fragrance of the life it renewed, but it had its scent; the faint exhalation of goodness. It would still come down upon the earth after man, destroying himself, had destroyed also the leaves and the grass. Its goodness might even renew again the face of the burnt and blasted earth. He did not know. But unlike Job’s comforters he believed there was a supreme goodness that could renew his own soul beyond this wasting sorrow of human life and death. (126-127)

In the book of Job, Job’s friends give him poor advice, neither truthful, loving, nor understanding. Though Job gives his own speeches, his friends respond from their own shortcomings rather than listening with compassion. Goudge’s characters also respond clumsily to each other at first. In particular, Mary knows immediately when she has said the wrong thing and caused a distance between herself and someone else. So, she grows in her capacity to see others for who they really are, and listen to them with the ear of her heart. One character reflects, “Understanding is a creative act in a dimension we do not see.” (194) Mary realizes that “love alone doesn’t go far enough….It must be charged with understanding.” (201)

In her cousin’s diary, carefully preserved for her, Mary reads:

I expect the winter will be hard…I shall be ill, as I always am, with the vile asthma and bronchitis, and I shall fall into black depression, and perhaps desperation too, but it will pass and the spring will come with celandines and white violets in the lanes, and then the late spring with bluebells and campion and wistaria coming out. And I shall learn the spring by heart, and then the summer, and I’ll learn the [church] bells and birdsong by heart, and the way the moonlight moves on the wall and the sun lies on the floor. (118-119)

To learn the spring by heart, to know intimately the ephemerality of fickle spring, is to accept the constant transformation of the seasons. It’s to accept the perpetuity of growth and change. The scent of water, for Goudge’s characters, comes when they confess their self-deceit. Only in this freedom can they be open to new life:

“What is the scent of water?”

“Renewal. The goodness of God coming down like dew.” (326)

Conclusion

The Scent of Water is a gentle, quiet story about interior lives being transformed. It shows the hard work of repairing the inner life after loss, grief, and suffering. Mary leaves the entrenched shell of her life in London for “the sheltering of God’s hand.” (72) It’s in this cloister under God’s hand that Goudge’s characters have the freedom to sort out their inner lives and, “under no compulsion…deliberately [choose] the path of peace.”9

In their own ways, Goudge’s characters learn to live “faithfully a hidden life,”10 as George Eliot’s wisest Middlemarch inhabitants do.

, writing about Beth March in Little Women, calls her life “a gentle invitation to embrace our hiddenness as a necessity to a kind of virtue—to live before the loving gaze of our Heavenly Father.” So is The Scent of Water an invitation to live in “the sheltering of God’s hand,” where we are hidden yet not unseen. The Scent of Water is populated by Beth’s literary kindred, the quiet ones, the noticing ones, the ones suffering from chronic mental and physical pain. If you long for a novel to settle you into the hush of spring, consider reaching for The Scent of Water to learn the spring by heart.For Further Reading

The Scent of Water by Elizabeth Goudge

The Joy of the Snow by Elizabeth Goudge

Beyond the Snow by Christine Rawlins

hosted by Julie WitmerI had originally included George Eliot here because I had somehow become convinced she was a daughter of a clergyman. Thanks to Brad for fact-checking this for me and correcting my mistake!

All quotations come from The Scent of Water by Elizabeth Goudge. New York: Coward-McCann, 1963, first American edition.

Also named Mary Lindsay, though I will refer to her as the cousin here to avoid confusion.

The illness is never named, and experiences of it are recounted in the cousin’s diary. One thinks of OCD as well as profound depression. The telling is profoundly compassionate, not only on Goudge’s part, but on her character’s loving gaze on her past self while ill.

Charles Adams is not a murderer, just a prodigal who regularly wrings the soft heart of his father for money. Genesis 4:1-16

Most frequent is n*****, used in the phrase “work(ed) like a n*****.”

Other writers with experience of Victorian violence toward children, like Charles Dickens, have the wisdom to treat is as wrong. Goudge mentions it happening in some of her novels, like Towers in the Mist, without much effect on her characters or plot; yet, she doesn’t describe it in detail or use it to show corruption of her characters, as George MacDonald did in The Maiden’s Bequest. See the comments from Juli Witmer (Elizabeth Goudge Book Club) below for an alternate and considerably more knowledgeable perspective!

John 4:7-14. The final line of The Scent of Water: “‘It’s a new little ship sailing out on living water.’” (349)

“That Mrs. Baker was accustomed to be obeyed she could see already, yet she felt that Mr. Baker was no yes man. He obeyed under no compulsion but because he had deliberately chosen the path of peace.” (44) Mr. Baker emerges as one of the most independent and artistic background characters in The Scent of Water. His story hints that, for Goudge, creating art is a matter of obedience: self-expression comes second after obedience to the work.

“[Dorothea’s] finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” Final paragraph of Middlemarch by George Eliot, published in 1871-1872.

This is such a beautiful reflection, Melody, on one of my favorite novels. I love this: “One character reflects, ‘Understanding is a creative act in a dimension we do not see.’” Some of my favorite characters in literature are the hidden, quiet ones. I think of Septimus Harding in Trollope’s Barsetshire series. I love that you come to an understanding here with Goudge in her human flaws. It’s such a fascinating conundrum, fallen humans creating transcendent art.

Thanks for introducing me to yet another author I'm piqued to read.

For me, your most thought-provoking comments came from your discussion of Goudge's human flaws. It reminded me of my Lenten book, Marilynne Robinson's "Reading Genesis." After recounting the sordid story of Jacob and Rebekah duping Isaac and Esau out of the birthright and paternal blessing, Robinson writes:

"Could history have taken its appropriate course if Jacob had dealt righteously with his father? Did he have that option? What becomes of moral judgment if an unrighteous act works for good, without or despite the actor's intention?" She concludes, "The covenant is not contingent upon human virtue, even human intention. It is sustained by the will of God, which is so strong and steadfast that it can allow space within providence for people to be who they are, for humanity to be what it is."

P.S. Thanks for the GE quote (from some of the most epic paragraphs in English lit).