Endō Shūsaku (1923-1996), known for his masterful novel Silence, spent his career writing about his beloved, beautiful land of Japan and its people, and the complexity of their encounter with the Christian faith. Silence and some of his other novels explore the persecutions of Kirishitans (Japanese “hidden Christians” in the 1500s-1600s) and contemporary questions about faith. In Sachiko, Endō wrote an account inspired by his generation’s experience of WWII. As Silence’s thousands of readers know, Endō never settles for easy answers, if he gives any answers at all. But in Sachiko he interrogates God about the problem of violence and suffering from his own generation.

Sachiko: The Novel and Its Setting

Nagasaki is the largest city in the Nagasaki Prefecture in the very southwestern tip of Japan. For centuries, while Japan was closed to the outside world, Nagasaki was the only point of contact for Dutch and Portuguese traders. Portuguese missionaries, like the Jesuit priest Sebastião Rodrigues in Silence, shared their Christian faith with local Japanese people, though being a Japanese Christian was illegal. Despite intense persecution, Christianity in Japan survived.1 Nagasaki remained the center of Japanese Christianity after 1853, when Japan opened to the West under intense pressure.

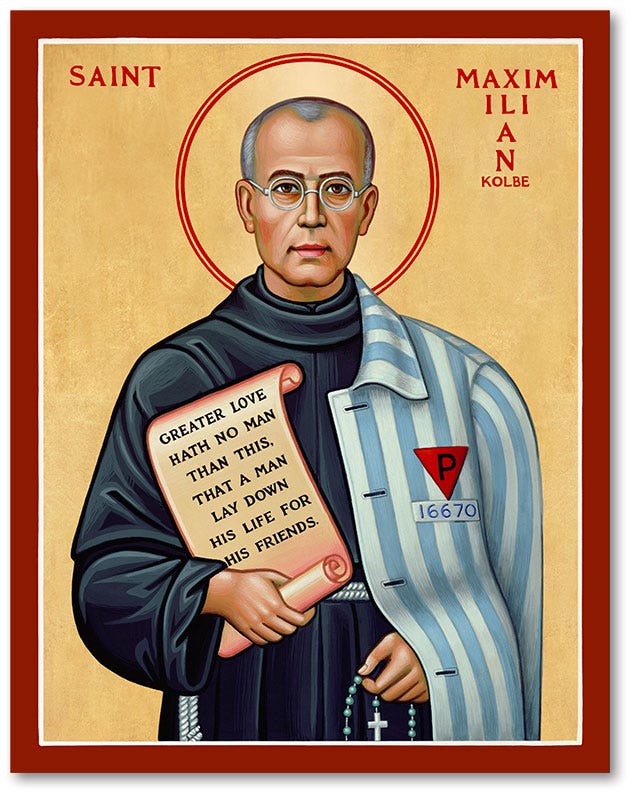

This is where we meet the characters of Sachiko in 1930. Nagasaki is a bustling harbor/factory town, and Ōura Cathedral has recently welcomed a Polish priest, Father Maximilian Kolbe. Sachiko, our main character, is a young girl who comes from a long line of Japanese Christians. The stories of the martyrs shape her imagination as she grows up, befriends the children of American expats, and curiously follows a young troublemaker, Shūhei.

Early in the novel, Father Kolbe gives Sachiko a bookmark with an image of the Pieta that said in Japanese, “Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”2 There is no special connection between Sachiko and Father Kolbe; he speaks little Japanese. He forgets he has given Sachiko the bookmark, and later gives her another one. Yet, this quotation from John 15:13 remains with Sachiko. As she grows into a teenager, she craves romantic love, but is there a greater love than that? “Mom,” she asks a few pages later, “loving someone is different from just caring about them, isn’t it?”3

Shūhei

Years before the invasion of Poland, Japan was at war with China, advancing on lands across Asia to expand the Land of the Rising Sun. Endō writes of the 1930s, “Though none of the people could say anything concrete about what would come of Japan, there was a sense that everything was advancing in a direction that would lead to something deeply tragic, and that sense planted a foreboding of gloom in the people’s hearts.”4 Arrests of Communist Party members and a renewed suspicion of Western culture led to further suspicion of Christianity, not just Western missionaries like Father Kolbe, but even Japanese Christians like Sachiko.

Despite his mischief-making youth, and the growing challenges of being a Japanese Christian, Shūhei decides to study literature at Keiō University and live in a dorm for Christian students.5 Though Shūhei’s personality is naturally given to fun and adventure, he recognizes that his world is changing, and what he wants from life might not be what he will get.

On a visit home, Shūhei and Sachiko visit the ruins of Hara Castle,6 where thirty thousand Christians had taken refuge before being slaughtered.7 “Sachiko could almost smell their blood in the cries of the cicadas, sounds she felt were reverberating from the lowest of hells.”8 What had love asked of these thirty thousand people? And what would love ask of her?

Father Kolbe

Meanwhile, Father Kolbe left Japan. He stands apart from the other characters, because he is not fictional, but a real historical figure. Endō follows the real contours of his life and supplies a fictional inner life for the Polish Franciscan who made it from Poland to Japan (and China and India) and back, where he helped to turn his monastery into a temporary hospital.

In 1941, Father Kolbe’s monastery in Poland was shut down by the Nazis, and Father Kolbe was arrested and taken to Auschwitz. This is where Endō shows Father Kolbe to us again in the narrative, among prisoners in Auschwitz who watch black smoke rise from death chambers.

“Then why does God ignore the black smoke in silence? Why doesn’t he put a stop to it?” [a prisoner asked Father Kolbe.] “If God is someone who closes His eyes to that black smoke as it consumes women and babies, I refuse to believe in Him.”

He turned to face the priest. “Father, why aren’t you answering?”

A look of pain fluttered behind the lenses of Father Kolbe’s thick glasses.

“I…I can well understand…how you feel,” he feebly responded to the man. “And yet…it seems to me that God has given to man something that can triumph over the black smoke from the gas chambers.”

“Given us something that can triumph over the black smoke?…And what would that be?”

“The…the will to love.”

Looks of unutterable contempt twisted the lips of the prisoners, and they turned their heads away. Their expressions clearly displayed their sense that there was no longer any point in talking with this hard headed cleric.9

Father Kolbe’s words seem ineffective, but they get under the skin of Henryk, a fellow prisoner. Even the act of sharing bread between prisoners on a starvation diet is enough to witness to him the existence of love:

“Father, I don’t believe in heaven. But I do believe in hell. This is hell.”

“This is not yet hell. Hell is…Henryk, hell is a place where love has utterly died out. But love hasn’t perished here yet….No matter how terrible the circumstances or the situation…men can still perform acts of love. That’s what I realized.”10

In Auschwitz, retaliation is made when a prisoner escapes. As ten men are selected for death by medical experiment, one cries out for his family. Father Kolbe steps forward to take his place: “Would you please let me die in place of this prisoner?”11 The SS officer grants his request. Father Kolbe’s final witness is an act of love, a testimony louder than any words he spoke in his life.12

Endō pushes his characters to extremes in Sachiko. Father Kolbe’s story ends prematurely, halfway through the novel, a witness to the choices that are to come for Sachiko and Shūhei.

“Once You’ve Read Literature…”

Though he can delay for a time as a university student, Shūhei knows he will have to serve Japan in the military. He struggles with how his faith and his studies have changed his view of war. Shūhei says to a friend, “When you kill another human being, you’re wiping out every part of that man’s life. Once you’ve read literature, there’s no way you can cancel out another man’s life.”13

In the decorated chocolate box where Sachiko keeps the bookmarks from Father Kolbe, she adds a poem by Satō Haruo that Shūhei gave her: “I was able to learn the meaning of true love from the heart, / It is a love that seeks nothing.”14 Sachiko wants to interpret this as Shūhei’s love for her, but like Shūhei she feels the draw of a larger love, the “greater love” she learned from Father Kolbe.

As Shūhei trains to be a pilot, he learns that there is another path for him than bombing civilians in other nations, something his conscience can no longer allow. He writes his priest:

Through my reading of literature, I came to understand that every person has a life of real depth. Even if it seems like there’s nothing in a person’s exterior to recommend them, I learned that each person, along with their pains and sorrows and joys, has hopes and prayers that accumulate like a geological layer in the depths of their swamp-like core.15

Like Father Kolbe, Shūhei chooses to lay down his life for another’s.

Conclusion

At the end of Sachiko, only Sachiko is left. She survives the atomic bomb on August 9, 1945, which pierced the heart of Christianity in Japan.16 Shūhei has perished in the war, as has Father Kolbe. Decades later, Sachiko is the mother of teenagers who think she doesn’t understand the deep questions of life. Endo concludes with her prayer: “These pains and sorrows sometimes made me doubt what was truly your will, but those doubts even now prod me to seek after you.”17

In Sachiko, whose depth and breadth I have barely scratched here, Endō allows no one to be considered “other.” He takes us into the minds of the Nazi who oversees Auschwitz and questions his eternal fate as he waits for Father Kolbe to die, into the mind of the Sachiko’s American friend who became the bomber of Nagasaki and idly wonders about his childhood friends as he destroys their city.

While Jesus in John 15:13 calls “greater love” laying down one’s life for one’s “friends,” Endō’s exquisite narrative layers onto this Jesus’ command to “love your enemies.”18 Endō’s experience of Christianity was full of enemies. His family’s Christian roots survived the fires of persecution for hundreds of years. His government turned against him as though Japanese Christians became Western upon conversion. His nation’s center of Christianity, Nagasaki, was brutally destroyed by a nation supposedly run by Christians. In some ways, Endō had more enemies—historically, culturally, politically—than friends. Yet, he writes in the way of love. In his writings, he does not foment anger or demand restitution for the pains of the past. Instead, he quietly seeks a better way forward. Ridiculous as the concept of love sounded in Auschwitz or in WWII Japan, Endō knew that laying down one’s life was the ultimate testimony to love.

If love is seeing the “lives of real depth” in everyone, then literature can help us do that: to see into the hearts of our enemies. It is easy to reject, to forsake, to abandon. In Sachiko, readers walk with Endō the hard way, the true way, the way of love.

Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region is a UNESCO World Heritage Site as of 2018.

Sachiko, 16.

Sachiko, 28.

Sachiko, 34.

Van C. Gessel notes that Yoshimitsu Yoshihiko (1904-1945), a Japanese Catholic philosopher, was the housemaster of Endō’s dorm when Endō was at Keio University. Shūhei mentions discussions with Yoshimitsu in the novel. Sachiko, 97. Endo says of him, “Yoshimitsu was a philosopher, a man of fiery faith and scholarly curiosity. He had studied in France under Jacques Maritain, exploring Christian philosophy, and then had returned to Japan. He was conversant not only in philosophy but also in literature and the arts, and when he dined with the dorm students, he spoke passionately with them about life and religion.” Sachiko, 129.

One of the World Heritage Sites mentioned above.

This historical event is reminiscent of the Maccabean martyrs recounted in 1 and 2 Maccabees.

Sachiko, 109.

Sachiko, 118. Ellipses original.

Sachiko, 127-128.

Sachiko, 196.

Father Kolbe was canonized in 1982. He is commemorated as one of the Modern Martyrs on the West Front of Westminster Abbey.

Sachiko, 134.

Sachiko, 257.

Sachiko, 367.

Nagasaki was a strategic target, as the home of the Mitsubishi Torpedo Plant, which was perhaps the world’s largest producer of torpedos at the time. It was the secondary target when Kokura, the original target, was obscured by smoke from the bombing of Yahata (among other reasons).

Sachiko, 404.

Matthew 5: 43-47 NRSVUE: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you: Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the gentiles do the same?”

I've been meaning to read Shūsaku but have been nervous to pick up Silence because of how intense it sounds. I might have to read this one first. Even though it also sounds intense, I've had a long devotion to St. Maximilian Kolbe. I visited his cell at Auschwitz with my family when I was in the fourth grade, and his story has been imprinted on my heart ever since.

Thank you Melody! This sounds like an incredible read. I haven't heard of it before, and I know very little about Japanese history or culture or its literature. Ack!